Diagnosis

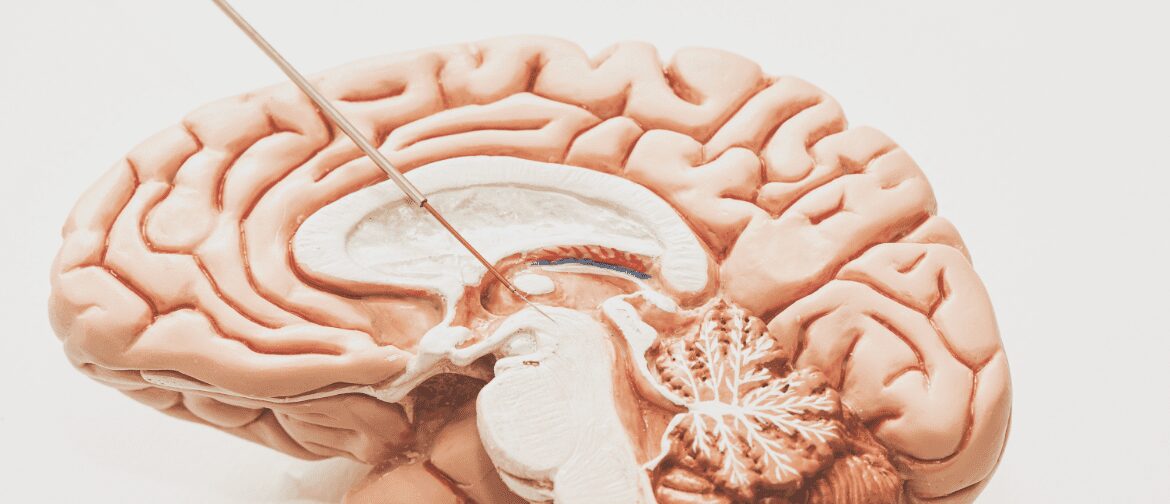

Early diagnosis of the disease can be challenging because there are no biomarkers, neuroimaging or other clinical tests available to confirm the diagnosis. PD diagnosis is currently based on the presence or absence of various clinical features and the experience of the treating physician.

The signs and symptoms present in early PD correspond to a number of other movement disorders, particularly other forms of parkinsonism, such as multiple system atrophy, drug-induced parkinsonism, and vascular parkinsonism, as well as diffuse Lewy body disease and essential tremor. Nevertheless, diagnosis of PD based on clinical features and response to antiparkinsonian medication can be achieved with a fairly high level of accuracy, particularly when made by a physician specializing in movement disorders (Pahwa et al., 2010).

Symptoms and Progression

Patients typically experience a very good response to levodopa during the early stages of treatment. As the disease progresses, however, the effect of levodopa starts to wear off. This phenomenon may be explained by ability of dopaminergic nerve terminals to store and release dopamine early in the course of the disease. With advanced stages and degeneration of dopamine terminals, the concentration of dopamine in the basal ganglia is more dependent upon plasma levodopa levels. Plasma levels may fluctuate erratically because of the short minute half-life of levodopa and the unpredictable intestinal absorption of this medication. Patients with moderate/intermediate and advanced PD start to be aware of a “wearing-off” or “end-of-dose” effect.

Intermittent or pulsatile stimulation of dopamine receptors is thought to be responsible for the development of the motor fluctuations and dyskinesias that complicate the long-term use of levodopa therapy in Parkinson’s disease (Nutt et al., 2000).

Motor fluctuations occur at moderate/intermediate and advanced stages of PD (see figure below). They are characterized by end of dose phenomenon or “wearing-off”, where patients have to reduce the interval between doses of oral medication (Olanow et al., 2001).

CHANGES IN LEVODOPA RESPONSE ASSOCIAted WITH PROGRESSION OF PD

SOURCE: (Medscape, 2016)

Motor complications occur in approximately 50 to 90% of patients with PD who have received levodopa for 5 to 10 years and constitute a major source of disability. These symptoms are especially common in patients with young-onset PD and tend to be seen more frequently in association with high doses of levodopa. In addition to the known side effects of levodopa therapy patients are subject to “on” and “off” periods. During “off” periods, patients are less able to control motor function. During “on” periods, motor function is “normal” and the blood plasma concentration of levodopa is optimal. Dyskinesias (i.e. involuntary movements) may be related to excessive concentrations of levodopa in plasma.

Treatment options

Therapies start, depending on the age of the patient, either with levodopa and/or dopamine agonists. In the moderate/intermediate phase additional therapies are added. Frequently, a combination including two or more of the following therapies is used: levodopa, dopamine agonists, COMT-inhibitors, optional MAO-B-inhibitors and/or anticholinergics. The moderate/intermediate and advanced phases often become more complicated to treat as patients have increasing periods of “off” time and levodopa-induced dyskinesias. In addition to the motor fluctuations during long term levodopa there may also be cognitive and/or psychiatric symptoms (Chaudhuri et al., 2013).

In the advanced In the advanced phase of the disease Continuous Dopaminergic Stimulation (CDS) is a commonly used therapeutic approach, while intermittent injection or subcutaneous infusion of Apomorphine, continuous enteral levodopa and deep brain stimulation have also been used.

Several reports and clinical trials have shown that when a loss of physiological dopamine is compensated for by levodopa, the resulting pulsatile stimulation causes alterations in the firing patterns of basal ganglia output neurons and leads to complications such as motor fluctuations and dyskinesia. Based on this, continuous drug delivery (CDD) represents an important strategy in regulating therapeutic efficacy for novel antiparkinsonian medications (Rascol, 2011).

The continuous infusion of a dopamine agonist is cumbersome for the patient and caregiver. However, it avoids the need for an intracranial operation and seems to provide benefits that are comparable with surgical therapies (Stocchi, 2008).

Guidelines

Early

Parkinson’ s

disease

Late

Parkinson’ s

disease

Parkinson’s

disease in

over 20s

An algorithm

for the PD

management

Practice

Parameter:

Treatment

Treatment

with

Apomorphine

About Dacepton®

Learn more about the potent, non-ergoline, non-selective and direct-acting dopamine-receptor agonist.

Patient Initiation

Learn more about What to consider, the Quick Titration and the Route of Administration.